The Endless Flow

In cities, demolition and reconstruction are ceaseless flows, transforming tangible structures as well as coexisting with us in visual mediums - photographs, films, banners, architectural visualizations (archviz), and more. These images foreshadow either imminent change or what has faded. Of these forms, photograph-like 3D rendering has become pervasive, dominating the cityscape and ubiquitously cloaking construction sites.

The world depicted in archviz is idyllic - always bathed in sunshine, peaceful, and immaculate. The stylish men exude confidence, the women grace and poise. Hipsters nonchalantly chat, couples walk their dogs in verdant parks. These utopian visions portray urban change as an unfettered march toward a gleaming future, enticing viewers with the promise that they, too, could inhabit this life. As architect Frank Ching described, “The viewer of a drawing relates to the human figure within it; he becomes one of them, and this is drawn into the scene...” Despite being fabricated, realism blurs our perception - virtual reality attains the status of actual experience and fact.

This archviz surrounding the construction site depicts the future of the Heygate Estate, which is currently undergoing gentrification.

Archviz presents a narrow, idealized notion of urban living. It homogenizes inhabitants’ socioeconomic status and demographics. This fosters exclusivity, indirectly suggesting that redesigned cities are for the wealthy, able-bodied, and socially conforming. Such uniformity contradicts places’ diversity, limiting accessibility and inclusion. It reflects and reinforces existing power dynamics rather than forging equitable communities.

An exhibition entitled “Designing People” at the University of California, Berkeley’s College of Environmental Design unpacked how the human figures populating these renderings (dubbed “scalies” by the curators for their original function of conveying scale and use of architecture) propagate societal standards across eras.

While the people depicted in this print were included just to convey a sense of size, researchers have found that their appearance and activities provide insights into daily life during 18th century. [1]

For instance, studies and golf signified men and the elite, while women were confined to domestic duties. All-white cityscapes morphed into diverse communities at officials’ behest, promoting integration. As curator Lowell put it, “The drawings were illustrating the architecture, but it was the people who were marketing an aspirational lifestyle. They were selling the idea to the client.” Notably absent are graffiti, rubbish, homeless populations, tattoos, and so on- archviz silently endorses a standardized vision of life. It veils an imbalanced power structure where elites’ interests override marginalized groups’ needs.

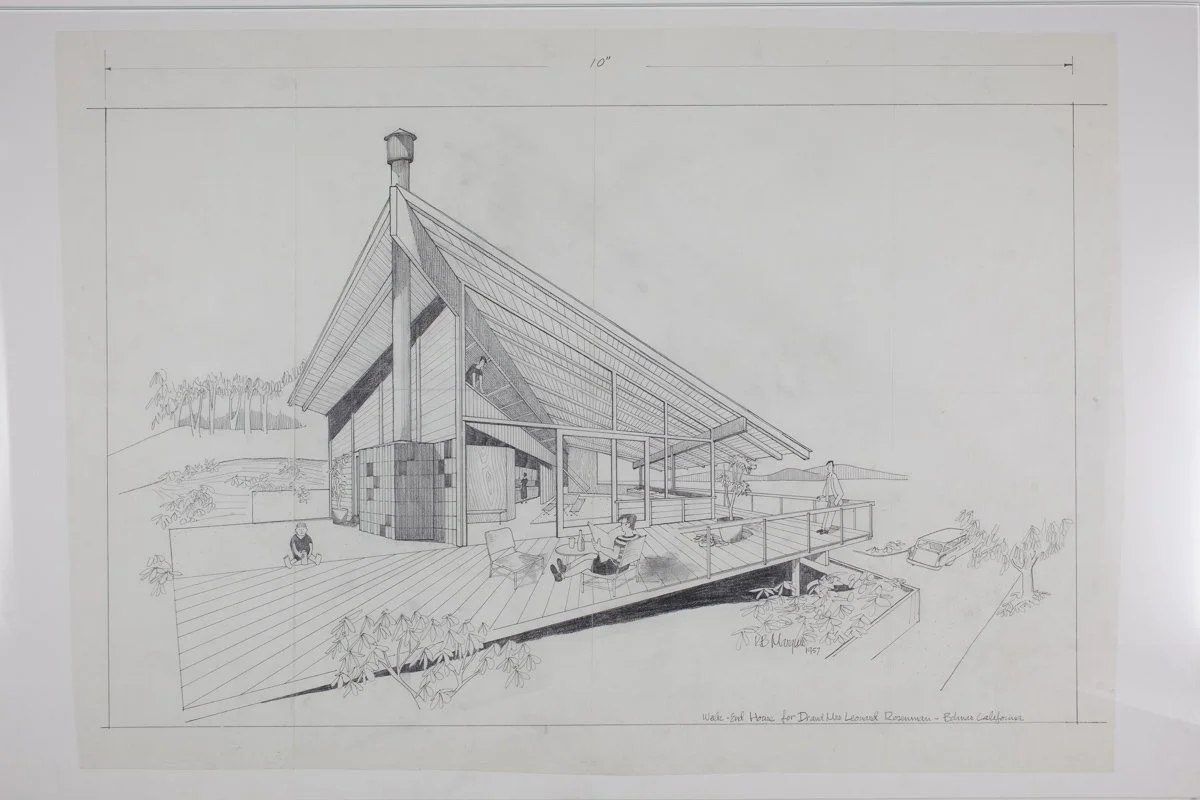

What goes unsaid in this portrayal of men absorbed in reading and leisure as children play outdoors is that the woman is isolated doing domestic work in the kitchen. [2]

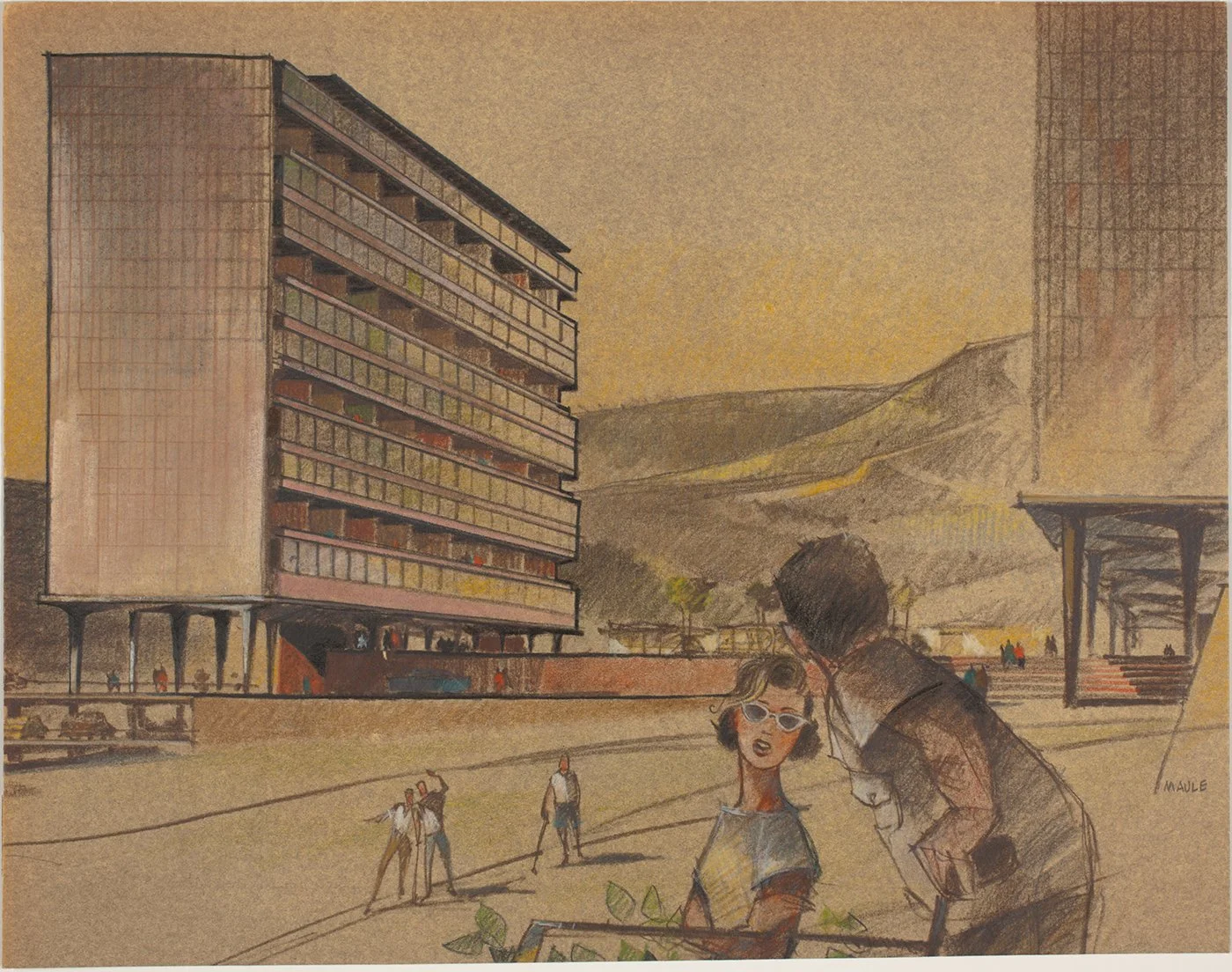

In this unidentified project from the mid-20th century, the depiction of three golfers between high-rising buildings raises an intriguing question of why they are shown in a non-golf setting. [3]

This echoes how photography was manipulated in 19th century Leeds, when medical officers of health appointed themselves as progress’ representatives to implement slum demolition of Quarry Hill. They had to shape the public views to suit their aims for support and rationality (To read more from “God’s Sanitary Law: Slum Clearance and Photography in Late Nineteenth-Century Leeds”). Photograph, seen as the transcription of “the reality”, was given the same status as “the truth”. Thus, it was used to align with the wills of the authorities, presenting what was unacceptable and not supposed to exist. The establishment has always molded prevailing ethics through visual media.

“The photography has never succeeded in narrative.”, stated John Szarkowski, the curator of the New York Museum of Modern Art Photography, in his introduction of the 1966 exhibition, The Photographer’s Eye. He referenced the American Civil War and World War II photographs, articulating that they had yet to explain what had happened without extensive captioning. “ The function of these pictures was not to make the story clear; it was to make it real.” (Szarkowski, 1996) Photography is, in fact, a highly de-contextualized medium, which is good at showing instead of telling. It relies on the translation of words and the interpretation of fields.

The examples demonstrate more than just the familiar trope of images manipulated to serve political aims. It highlights how the perceived evidentiary power of photography also parallels the realism of modern 3D rendering techniques as well as how the pattern continues in modern society, where archviz was deployed strategically amid demolition in this case.

In another paper "The Event of Void", the author describes the long-term vacant Heygate Estate[4] as "a machine to exhibit, a factory of images and imagination." The authorities utilize the flow of pictures to fill this vacuum period, turning Heygate into a "criminal" dragging down the community. Concurrently, they spread "the spectacle of the finally vanquished monster" through archviz. As the author states, "It is firstly its new image, and only secondarily its new material conditions, that will attract people and capitals from afar..." (Sebregondi, 2011) Archviz appears as the representative of promise, the hero, combating the unacceptable monstrous present. Archviz and photography complement each other, collaborating in this narrative construction. The whole show is directed and played by the same hands. The same rhetoric was used as when the government demolished the previous neighborhood to establish the Heygate Estate. The authorities once again leverage visual media's trait to shape societal norms aligned with their agendas.

This selection made by Francesco Sebregondi highlights representations of the Heygate Estate in mass media over the past decade or so. [5]

Ultimately, in people's minds, the simulacrum has been elevated to the sense of actual experiences. Photography symbolizes the present and past, while archviz points to the future. We readily embrace their utopian promises, even though these pristine renderings obscure imperfect realities, promoting biased agendas under the guise of progress. Unpacking the encoded biases embedded in archviz is essential as urban redevelopment accelerates globally. Not only archviz, but images are never innocent, and neither are we. It is a structure of complicity including every image producer and consumer. Images should be seen as a form of carefully constructed spectacle, where the power dynamic is underlying. Exposing archviz biases is just the other accusation against this spectacle. Remaining aware of these visual elements we approach in our daily is obligatory in today’s world. The endless image flow has just begun.

(2023/11/08)

Note:

A View of the Palace of Marfi,” Environmental Design Archives Exhibitions, accessed October 16, 2023, https://exhibits.ced.berkeley.edu/items/show/3362.

Marquis, Robert, 1927-1995 (Architect), “Rosenman, Leonard ,” Environmental Design Archives Exhibitions, accessed October 16, 2023, https://exhibits.ced.berkeley.edu/items/show/3331.

Maule, Tallie, 1917-1974 (Architect), “unidentified project,” Environmental Design Archives Exhibitions, accessed October 16, 2023, https://exhibits.ced.berkeley.edu/items/show/3314.

The Heygate Estate was a large housing estate located in Elephant and Castle, London. It was built in 1974 as a set of high-rise concrete apartment blocks containing over 1,200 homes. The estate fell into decline due to maintenance issues, design flaws, and socioeconomic problems. By the 1990s it had developed a reputation for crime and poverty. In 2010, the remaining residents were relocated and the buildings demolished between 2011-2014 as part of a £1.5 billion regeneration plan. The site is being redeveloped into luxury apartments and retail spaces. The demolition and regeneration of the Heygate Estate remains controversial, with critics lamenting the loss of affordable housing.

“Selection of stills from CRACKED EGGS (2007); HIP HOP OPERA (2007); FALLOUT (2008); Orange Rock Corps (ad – 2008); THE DISAPPEARED (2009); HARRY BROWN (2009); THE BILL (S.26 ep.13 – 2010); SHANK (2010); HEREAFTER (2010); Massive Attack – "Psyché" (2010); LUTHER (S.1 ep.02 – 2011); THE VETERAN (2011).” Selected by Francesco Sebregondi.

Reference:

UC Berkeley College of Environmental Design (2015). Designing People · Environmental Design Archives Exhibitions. Retrieved from https://exhibits.ced.berkeley.edu/exhibits/show/designing-people

2. Sebregondi, F. (2011). The Event of Void: Architecture and Politics in the Evacuated Heygate Estate.

Tagg, J. (2005). The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories. University of Minnesota Press.

Szarkowski, J. (1996). Introduction to The Photographer's Eye.

Lockemann, B. (2022). Thinking the Photobook. Hatje Cantz.